Flies can make agriculture considerably greener

The flies feed on waste and can be converted into protein-rich cow and pig feed, almost without emitting CO2.

Denmark imports 1.6 million tonnes of soy each year. The vast majority of this soy is used in agriculture as feed for pigs, cows and chickens.

And it is an extremely effective feed. Soybean meal contains a lot of protein and has a unique composition of amino acids allowing for a high percentage absorption of the feed during animal digestion.

The only problem is that imports of soy have a negative impact on the climate. Brazil is felling rainforest to make space for ever more soy fields, and the long transport distance to Europe emits large amounts of CO2.

However, the good news is that researchers from Aarhus University may have found a replacement for soy. Flies! The larvae of flies contain large amounts of protein, which makes them an obvious choice for drying and milling into protein-rich meal. The meal can subsequently be used to make feed, explains Goutam Sahana.

He is a senior researcher at the Center for Quantitative Genetics and Genomics at Aarhus University and head of one of the centre's fly projects.

"Using flies as a source of protein has many advantages. Insect production does not take up a lot of space, the larvae can feed off waste, and they emit only a small amount of greenhouse gases."

| Center for Quantitative Genetics and Genomics |

|---|

Together with 70 research colleagues at the Center for Quantitative Genetics and Genomics, Goutam Sahana is working to improve the way in which we breed animals and plants today. With the help of large statistical models, researchers at the centre identify the genetic traits in animals and plants valuable to agricultural. For example, a valuable trait would be cows that produce less methane during digestion or produce more milk. Or a trait enabling a plant to better resist a certain type of pest. With the knowledge produced by Goutam Sahana and his colleagues, the agricultural sector can more easily breed animals and plants that are more sustainable and better geared for the green transition. Insect breeding, in particular, is an emerging research area that has attracted a lot of research funding recently. More than 20 nationalities are employed at the centre, where they work closely with industry and agriculture throughout the world. |

Fly farms in Denmark and Africa

Together with a number of research colleagues and private companies in Denmark, Kenya and Uganda, Goutam Sahana is currently conducting trials using flies for feed.

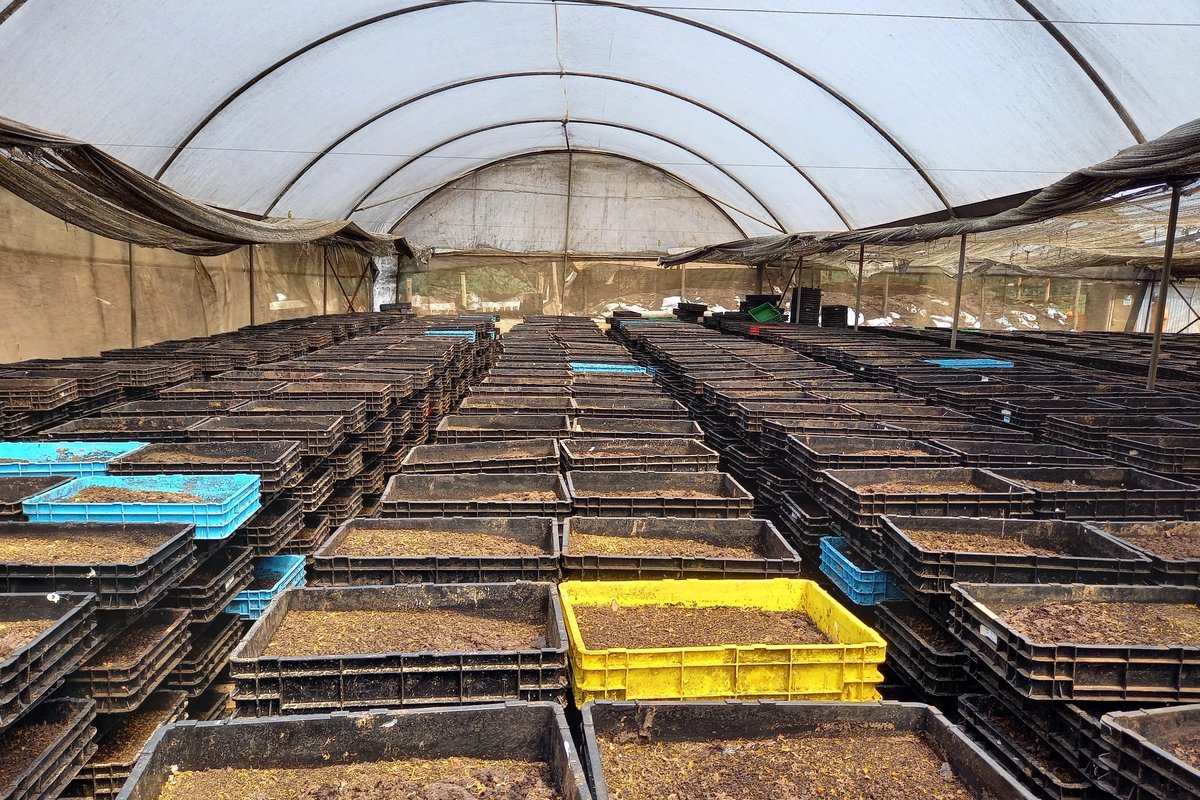

As opposed to soybean, flies do not require many hectares of soil. All they require are small hothouses and waste to feed on.

"We produce flies by placing a number of adult flies in small hothouses. They don't eat. They mate, lay eggs and then die. When the larvae hatch, they eat the waste that we give to them," he says.

When the larvae reach a certain size, the researchers kill 99% of them, dry them and mill them into a protein-rich powder that can be used for animal feed.

Because each fly lays a huge number of eggs, there is only need to save one per cent of the larvae. These are allowed to grow into adult flies for mating and producing the next generation of larvae for animal feed.

About breeding flies

It may all sound very easy, but the researchers still have to eliminate a number of challenges before fly farms can be established on a larger scale.

One of these challenges is how to control the breeding of flies, explains Goutam Sahana.

"With domestic animals, it’s easy to measure the effectiveness of our breeding work. For example, we can measure how much milk the individual cow yields. We would then inseminate and breed the cow that gives the most milk. This is not an option with flies," he says and continues:

"We can't observe and monitor the individual fly. There are thousands of them, and it’s impossible to tell them apart. Instead, we work with a technology to monitor the flies at family level. With the help of cameras and artificial intelligence, we identify the families who produce most eggs and grow the fastest."

Right now, Goutam Sahana is heading a number of experiments, the first of their kind, to develop the technology to accomplish exactly this.

"We're not there yet, but we hope that, with the use of cameras and various sensors in the insect farms, we will be ready to start breeding the flies. Once we’ve accomplished this, improving production will go fast.”

Black soldier flies

Goutam Sahana and his colleagues are not trying to breed just any fly. There are more than 110,000 different species of fly in the world, but the black soldier fly is particularly suitable for breeding and production. Therefore, they have selected this fly for their experiments.

The black soldier fly, which lives naturally in Africa, the southern part of the USA and elsewhere in the world where it is hot and humid, contains a lot of protein as well as a series of micronutrients that are good in feed.

As opposed to the soy plant, protein from black soldier flies can be harvested many times a year. It takes less than three weeks from the eggs have been laid until the larvae have fatten and are ready to be converted into feed.

Furthermore, each fly lays between 300 and 600 eggs. Establishing a production of scale is therefore quickly accomplished, and since the fly’s generation time is so short, breeding can be commenced fast once Goutam Sahana and his colleagues have figured out how to identify and monitor for the best hereditary genes.

Feeds off waste and faeces

Another advantage of the black soldier fly is that its larvae can eat virtually anything. Food waste, residual products from slaughterhouses, slurry and even human faeces are delicacies for the larvae.

In Denmark, there are strict rules on what can be used for animal feed. But that is not the case in Africa. In Africa, several farmers and companies are already utilising waste from slaughterhouses, and faeces from chickens and humans to feed flies, says Goutam Sahana.

"The black soldier fly can eat virtually anything, but there’s a difference in how much protein is produced in the end. Some of the things we’re trying to find genetic markers for, and breed for, are traits that make the flies more resilient to bacteria and other microorganisms in waste and faeces," he says.

For fly production to pay off and deliver enough protein, it is important that the larvae grow fast and that as few as possible die prematurely.

"The more waste products we can feed to the flies, the more sustainable the production will be. Imagine if we can breed flies that can transform virtually any organic waste material into feed protein?" he says.

A super sustainable production

If Goutam Sahana and his colleagues are successful in their efforts to develop an effective breeding technology for the flies, farming them could very well become entirely circular.

That would mean the fly farms would not consume more resources than they give back to nature," Goutam Sahana explains.

"The fly larvae can live off of the waste that we don’t know what to do about. And we can use the residual products from farms as fertiliser in fields. In other words, there would be no waste products from the production," he says.

The only challenge of farming black soldier flies in Denmark is that they need a fairly hot climate to thrive. Preferably high summer temperatures.

"The flies and the larvae need a climate of 25-27 degrees Celsius, but the larvae almost produce enough heat on their own, so we only need a little energy to heat the hothouses. And the little energy required will have to come from renewable energy, of course," he says.

Contact information

Goutam Sahana

Senior scientist at the Center for Quantitative Genetics and Genomics

Mail: goutam.sahana@qgg.au.dk

Tlf.: +45 30 57 71 59

Jeppe Kyhne Knudsen

Journalist og science communicator

Mail: jkk@au.dk

Tlf.: +45 93 50 81 48